Diversions: France

Topic: Travel

Diversions: France

A slow afternoon in Hollywood, and thinking it may be time for another visit to catch up with Ric Erickson, editor of MetropoleParis - haven't chatted with him face to face in a few years. But on the right is not April in Paris. It's a December day in 2001, from the Pont des Arts, walking back to the hotel in Saint Germain, glancing up to the southwest. Rooftops and that strange tower. It's not Hollywood, or even Paris Las Vegas.

Later, from the hotel window, light in the heart of the left bank - l'église St-Germain-des-Prés in the afternoon traffic, and in the second chapel of this church a stone marks the spot where philosopher Rene Descartes is buried. The abbey here was founded in 558. It was rebuilt between 990 and 1021, and restored again from 1819 to 1823, thanks to Victor Hugo (see a history here and the current website here). To the left is Les Deux Magots - Fréquenté par de nombreux artistes illustres parmi lesquels Elsa Triolet, André Gide, Jean Giraudoux, Picasso, Fernand Léger, Prévert, Hemingway, Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, pour ne citer qu'eux, il accueillit les surréalistes sous l'égide d'André Breton, bien avant les existentialistes qui firent les belles nuits des caves du quartier. Jim Morrison of The Doors frequented this same café it's said - Morrison was buried in Paris of course. This intersection, Boulevard St-Germain at rue Bonaparte, is a good place to be. Drop a line for details - a good jazz club, odd shops, goodies in the Buci market a few blocks to the right.

That's Paris. But a pleasant train ride north, just an hour or two, is Rouen, in the heart of Normandy. It's old in a different way. This was June afternoon, six years ago. Sip some calvados. Good place.

Way south. Everyone associates Arles with Van Gogh, of course. But drive down from Avignon, through St-Remy (visit the asylum where Van Gogh spent some time after he cut off his ear), through Les Baux (a mountain fortress town that has an odd history having to do with Richelieu and the Huguenots, and metallurgy, as aluminum ore, bauxite, is named for the place), and you finally get to Arles. It's old in a different way - Roman. This is the old coliseum, the same summer. They use it now for French bullfights, the kind where the bull lives. You get good light and shadows there, and that means it's been in a few movies, as right here John Frankenheimer filmed that shoot-out in Ronin - so if you're not into art, or bullfighting, or Roman history, there's always the Hollywood angle, as Robert De Niro was here too.

After They're Dead

Topic: Historic Hollywood

After They're Dead

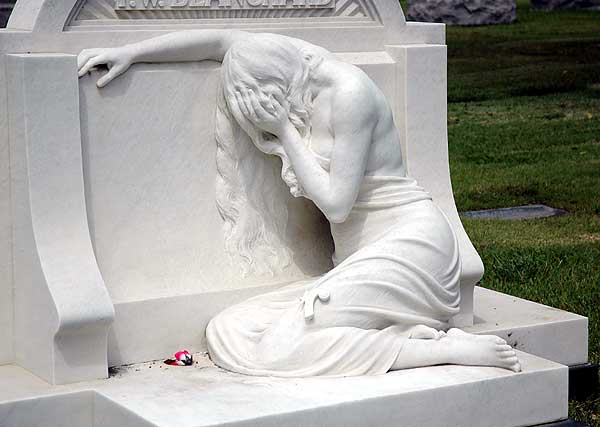

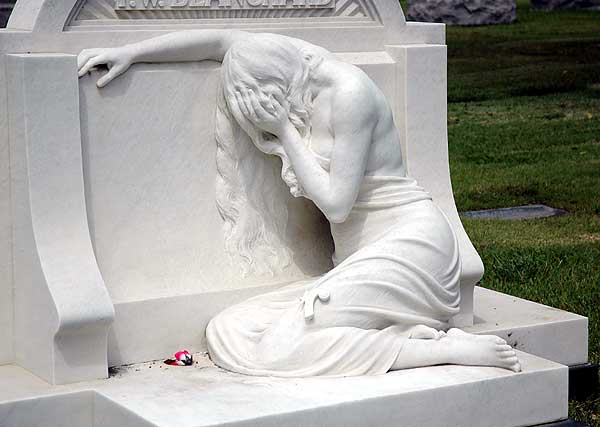

A few sites of interest out here, like this (right), "The Keeper of the Watch" at the Hollywood Forever cemetery down on Santa Monica Boulevard, just behind Paramount Studios. This is at the complex of monuments related to the Los Angeles Times - the first being the grave of Harrison Gray Otis. Otis started the paper. Next to that, the tomb of his son-in-law, Harry Chandler, who ran the paper until his death in 1944, and Otis' daughter Marion Otis Chandler, and next that a massive monument to the victims of "The Crime of the Century" - the twenty who died when the Times was bombed in October 1910.

A few sites of interest out here, like this (right), "The Keeper of the Watch" at the Hollywood Forever cemetery down on Santa Monica Boulevard, just behind Paramount Studios. This is at the complex of monuments related to the Los Angeles Times - the first being the grave of Harrison Gray Otis. Otis started the paper. Next to that, the tomb of his son-in-law, Harry Chandler, who ran the paper until his death in 1944, and Otis' daughter Marion Otis Chandler, and next that a massive monument to the victims of "The Crime of the Century" - the twenty who died when the Times was bombed in October 1910.

Otis hated unions and ran an "open shop" - his workers would never band together and pressure him for anything. Unions were evil. And Otis made a lot of enemies scoffing at the "rights" of the working class. The price was the Times building leveled by a bomb, and the dead.

See this, drawn mainly from Graham Adams Jr., Age of Industrial Violence, 1910 York: Columbia University Press, 1966 -On 1 October 1910 the Los Angeles Times building exploded under mysterious circumstances. The blast was felt throughout the area. One survivor said, "Frames and timbers flew in all directions. The force of the thing was indescribable." Employees of the Times tried to escape the flames, and some jumped from windows without safety nets below. A few hours later, nothing remained but smoldering debris. Twenty people died in the explosion.

Harrison Gray Otis, the antiunion publisher of the Times, blamed organized labor and dubbed it "The Crime of the Century."

Organized labor responded by blaming Otis, asking, "Are his own hands clean?" AFL president Samuel Gompers disavowed union participation in the tragedy, arguing that urban terrorism would actually hurt labor's cause.

Famous detective, William J. Burns was hired to investigate the blast. He played a hunch and was led to the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers (BSIW), located in Indianapolis, Indiana. Burns suspected that the union's secretary, John J. McNamara, had directed the attack. The detective set up a trap in a Detroit hotel on 12 April 1912 and arrested McNamara, his brother James, and another accomplice named Ortie McManigal. In McNamara's suitcase Burns found guns and six lock mechanisms similar to those used in Los Angeles.

On 12 July both brothers pleaded not guilty and set off a chaotic atmosphere in the courtroom. Clarence Darrow, one of America's most famous lawyers, represented the McNamara brothers, although reluctantly, because he felt the prosecution's case was. solid. After the first month the attorneys had selected only eight jurors and showed no signs of hurrying the process. On 1 December 1912 the defendants dramatically reversed their pleas. James pleaded guilty to the Los Angeles explosion, while John answered to a lesser charge in a separate bombing. Darrow explained the decision: "It was our only chance... It was in an effort to save J. B. McNamara's life that we took the action."

Judge Bordwell, reacting to the public's outrage, sentenced James McNamara to life imprisonment and John to fifteen years of hard labor.

The McNamara case led to heavy financial losses and declines in membership for all Los Angeles unions. The public backlash hurt the AFL, and Samuel Gompers received criticism for supporting the brothers. Not only had the McNamara's blown up a building and taken lives, they also destroyed the labor movement in Los Angeles.

And it never really recovered out here. (Heck, the two had also blown up the Llewellyn Iron works in Los Angeles on Christmas day of the same year - they weren't nice men.)

The unions didn't really recover until Ronald Reagan started his anti-communist thing after World War II. In 1947 the Screen Actors Guild asked him to mediate between a few industry unions. He butted heads with Herb Sorrell, the head of the Conference of Studio Unions, who made no bones about his views on workers' rights, views that to some seemed communist. Reagan didn't like the guy. In 1947 the Screen Actors Guild elected Reagan their president, the first of his five consecutive terms, and then he testifies as a friendly witness before Joseph McCarthy's House Committee on Un-American Activities - and then the "Hollywood Ten" are off to prison and quite a few writers and directors are blacklisted, not to work in Hollywood for many decades. Harrison Gray Otis no doubt smiled from the great beyond.

Below, the militant eagle on the top of the monument to the victims of "The Crime of the Century" -

Directly across the alley from all this, a weeping figure.

Photographs - April 6, 2006

A few sites of interest out here, like this (right), "The Keeper of the Watch" at the

A few sites of interest out here, like this (right), "The Keeper of the Watch" at the

On the right, light and shadow on the new façade of

On the right, light and shadow on the new façade of

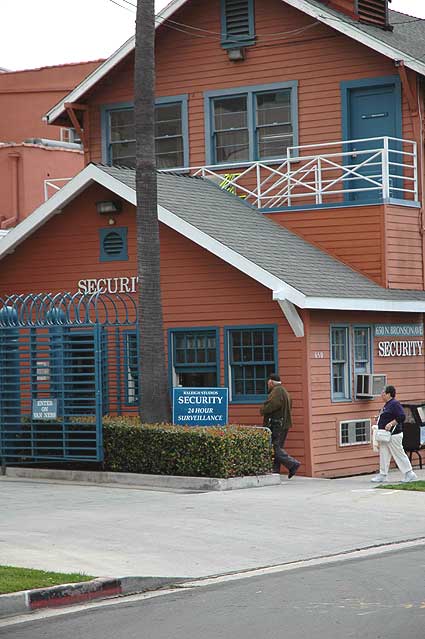

Thursday, April 6th, was a photo excursion - off to document Hollywood stuff, Paramount Studios down on Melrose, and more of old Hollywood, the dead celebrities at

Thursday, April 6th, was a photo excursion - off to document Hollywood stuff, Paramount Studios down on Melrose, and more of old Hollywood, the dead celebrities at